Mustanging and "Wild Horse Annie"

In the 1920s, with the advent of motorized vehicles and tractors, the value of horses, as a necessary component of man's way of life, declined. Few wild horses were rounded up, and, once again, their populations slowly increased. In some regions, wild herds became serious competitors with domestic livestock, for grass and water. Between 1920 and 1960, ranchers would frequently shoot free-roaming wild horses on sight (as did early U.S. Grazing Service range riders), eliminating large numbers of animals.

After implementation of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934, the open range was officially closed, grazing districts were formed, and grazing permits allocated. While this legislation was designed to "stop injury" to the unregulated public rangelands by "preventing overgrazing," and to "provide for orderly use, improvement and development," it also spawned in the permittees an increased sense of territorialism and, perhaps, a less generous spirit toward what they now saw as "wild horse intrusions." The Grazing Service and the ranchers sought to eliminate wild horses from grazing districts. During World War II, 77,000 were removed from the public lands "to control their numbers," but Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes would not allow total removal of the herds.

More notably, during this period, mustangs became an economic asset as pet food and fertilizer. Commercial hunters for the pet food processing plants moved in, and, within a brief span of years, did what the rancher and his occasional shooting spree had not been able to do, that is, seriously deplete mustang numbers in every state where they ranged. Horse removal served two purposes. It freed up grazing land for the ranchers, and horse carcasses provided cheap meat for the processors. Paid by the pound for horseflesh, mustangers were required to bring in large numbers of animals to glean even a modest living. Eventually, airplanes came into common use, along with trucks, to expedite roundup. Since the animals were on their way to slaughter, they were viewed simply as "meat-on-the-hoof." Humane handling and transport were set aside. Motorized mustanging operations were described as "bloody, brutal, and repulsive."

On a "memorable day in 1950," a Nevada rancher's wife named Velma B. Johnston came upon a truckload of mutilated horses as she was driving from her ranch near Reno. She discovered that these horses were wild, having been captured in an airborne roundup. Their destination was a slaughter house. The sole requirement was that they be "ambulatory and plentiful." The captors received 6.5 cents per pound, and because net profit depended upon quantity rather than upon condition, injury to the animals was of minimal concern.

For many years, Mrs. Johnston had heard about the capturing of wild horses by airplane. "This practice concerned me," she wrote, "but it had not touched my life directly. I pretended it didn't exist, hoping it would go away." However, after that fateful day in 1950, Velma B. Johnston (who would later gain the appellation of "Wild Horse Annie") could no longer "pretend it wasn't there." In the decades to come, wild horse issues would occupy her days and change the lives of many others who took up her cause. By 1950, only 25,000 wild horses were left in the American West, and the commercial harvest was still in full force. However, now the wild horses had a determined but gentle, and politically skillful, ally in "Wild Horse Annie" and in the alliances and organizations that formed around her in support of her movement to protect and save America's remaining wild horses.

McCullough Peaks herd area

Protective Legislation

In 1952, Velma B. Johnston's own Storey County, Nevada saw the first legislation passed to prohibit the capture of wild horses and burros by means of airborne and mechanized vehicles. Just three years later, she pushed through legislation at the state level, but an amendment specifically prohibited the legislation from applying to public lands, which, then, included 86 percent of Nevada. It became obvious that only federal legislation would halt the "massive clearance programs..." of wild horses on western rangelands. After a prolonged and bitter battle, however, the "Wild Horse Annie" bill passed through Congress and was signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on September 8, 1959. This law prohibited the use of aircraft or motorized vehicles to hunt wild horses and the pollution of their watering holes, on all land belonging to the United States. However, the animals could still be killed, and wild horse roundups continued, some using illegal aircraft. Wild horse numbers continued to fall.

Therefore, even more encompassing legislation was sought by wild horse protectionists. The International Society for the Protection of Mustangs and Burros was founded in 1965, an organization that immediately took up the task of conceiving and developing more effective wild horse and burro legislation. In 1968, the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range was established on the Wyoming-Montana border to protect a small herd of about 200 wild horses. Creation of this wild horse refuge, coupled with the earlier development of a wild horse range at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada in 1966, gave impetus to the wild horse movement. On December 15, 1971, President Richard M. Nixon signed the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burro bill into law, calling wild horses and burros "...a living link with the days of the Conquistadors, through the heroic times of the Western Indians and the pioneers, to our own day when the tonic of wilderness seems all too scarce." It was now a federal crime to kill or harass these animals on federal lands, with fines presently at $100,000 per horse or burro, plus up to one year in jail.

Rock Spring round-up

The Controversy

Federal protection for wild horses has, over time, fueled the wild horse controversy. It placed the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in the uncomfortable position of satisfying its historical constituency -- ranchers and land users -- while managing and protecting wild horse herds within 11 states throughout the Great Plains.

Animal welfarists view wild horses as a form of wildlife, worthy of native wildlife status, owing to the horse's 57 million years of evolutionary history in North America. Running free on the open ranges of the West, wild horses are seen by this faction as an aesthetic and historic resource, worthy of protection and deserving of their own place under the sun.

However, a majority of ranchers, and most wildlife biologists, consider wild horses a scourge on the landscape, "weeds," to be controlled or eliminated -- nothing more than a domestic livestock species gone "feral." Ranchers resent the intrusion of the federal government in wild horse matters that were once, essentially, left to the ranching community and local public land agency range managers. The aesthetic "wild horse lovers" are viewed as misinformed, unrealistic, and out of touch with the pragmatic problems of ranching -- elitists, who have the economic advantages of urban life but none of the liabilities of an agricultural operation. Wildlife managers see wild horses as intruders on wildlife habitats where more worthy "native" species hold, in their view, a priority status. Since passage of such acts as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)(1969-70), Federal Land Policy and Management Act (1976), Public Rangelands Improvement Act (1978), and "Full Force and Effect" regulations during the 1990s, the wild horse controversy has become even more heated and complex.

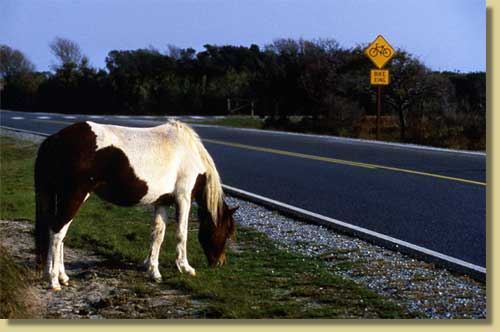

Assateague State Park

The controversy is fanned by such issues as ascertaining accurate wild horse numbers. While the BLM is mandated to conduct periodic censusing of wild horses within herd management areas, their censusing figures are constantly questioned by wild horse advocates, who feel the BLM inflates horse numbers, allowing the government agency to round up more horses than necessary. Wild horses are to be gathered only when ecological damage to rangeland ecosystems has been scientifically documented through range monitoring and habitat use. However, data to prove site-specific impacts of wild horses on grazing lands and riparian areas is expensive and difficult to obtain on a regular basis. Therefore, the BLM is often constrained by lack of data that, legally, allows horse removals. Its Wild Horse and Burro Adoption Program is fraught with difficulties -- a lack of adopters, nationwide; problems screening potential adopters and monitoring horses for care and cruelty violations after adoption; purported slaughter of wild horses, both before and after title transfer; too many unadopted horses in the "pipeline." Population control measures, through temporary chemical sterilization of wild mares, have been controversial. Wild horse protectionists resort to lawsuits against the BLM, on a periodic basis, to force changes in BLM policy or stop actions they feel are wrong.

Federal land management, with its multiple-use mandate and competing users -- each bringing different values into the equation -- is a monumental and, sometimes, nightmarish task. Utilitarians wish to benefit from and extract from the land for human use, while more aesthetic users want "wildness" and beauty, recreation and freedom. Are wild horses worthy or worthless? As John Muir wrote, "The battle for conservation will go on endlessly. It is part of the universal warfare between right and wrong."